Note: A version of this article was published in our LinkedIn newsletter, Pricing Power Clarity®.

Pricing power – defined broadly

In our previous newsletter installments, we proposed expanding the accepted meaning of “pricing power” to include the full toolset of pricing and offering design, as long as such actions drive gains in a company’s earnings metric. In this installment, we look in some detail at three pricing power moves to illustrate that consumer brands always have additional pricing power to find, nurture, and harvest.

Move #1: Targeted actions to “take price” intelligently

For many brands, important cost components will continue to erode the bottom line in 2023. With most brands taking some price increases in 2021-2022, signs of softening demand may be a looming reality for a variety of industries, brands, and sections of any given brand’s markets. What to do?

Increasing prices will remain a key component of a brand’s pricing power, but will need to evolve to its more intelligent forms. Blunt force price actions will need to be replaced with actions carefully designed to “thread the needle” and avoid collision with pockets of sagging consumer willingness to pay (WTP). Specifically, taking price intelligently will require careful selection of:

- Where: What products, markets & channels still offer favorable breakeven analysis and consumer behaviors / price elasticity patterns conducive for further actions?

- How: Should you attack highly visible list prices, selling prices, etc? Or should you operate somewhere else in the price waterfall (cutting discounts, eliminating “giveaways” like points and cash rewards, or reducing pack sizes)?

- Whom: Can you target actions to affect some customers but not others? For example, using surcharges or charging for returns to increase prices on higher cost-to-serve or inconsistent, long-tail customers?

Brands from Amazon to Zara are busy with such surgical actions, from reducing % cash back on Amazon credit card purchases, to raising delivery fees or purchase amount necessary to get free delivery, to charging fees for some or all returns. Every brand should have a thorough review of available levers, with a rank-ordered impact list and a deployment plan with clear timing and triggers.

Move #2: Monetize previously “lowly”, low-cost assets into pricing power that moves the needle

This “get creative, make something out of nothing” strategy is a favorite of ours. It reflects a brand’s attitude that it should leave no stones unturned, no assets unutilized, no previously held beliefs unchallenged. It finds and harvests additional pricing power in unexpected places, whether with surgical tactical offers, or with transformative strategy twists.

Recall that we purposefully defined pricing power broadly, to include all measures with pricing and offering design that drive our target profit & valuation metric. Now consider these examples:

Example: Netflix’s decision to finally adopt ad-supported, lower priced plans:

I wrote extensively at the time about the brilliance of Netflix pricing power move. It finally monetizes the previously ignored assets that were there all along: value to 3rd party advertisers of Netflix’s patient, glued-on customer eyeballs, made even more valuable by extensive data and preferences-targeting AI. Plus: the customers-in-waiting that would convert at a lower price point (often an “invisible”, “lowly” perception asset, because human decision makers undervalue foregone gains, and overvalue fear of loss “this will cannibalize our existing customers!”). Technically introducing a lower-priced package could qualify as a “price decrease” if only list price was concerned … except Netflix finally realized it can harvest pricing power by including 3rd party dollars in its understanding of “price”!

Netflix picked up tens of billions of dollars in market cap since, and reported $7.7M new subscribers in the first quarter since the move – its best growth news reversing a couple of years of sagging or negative growth.

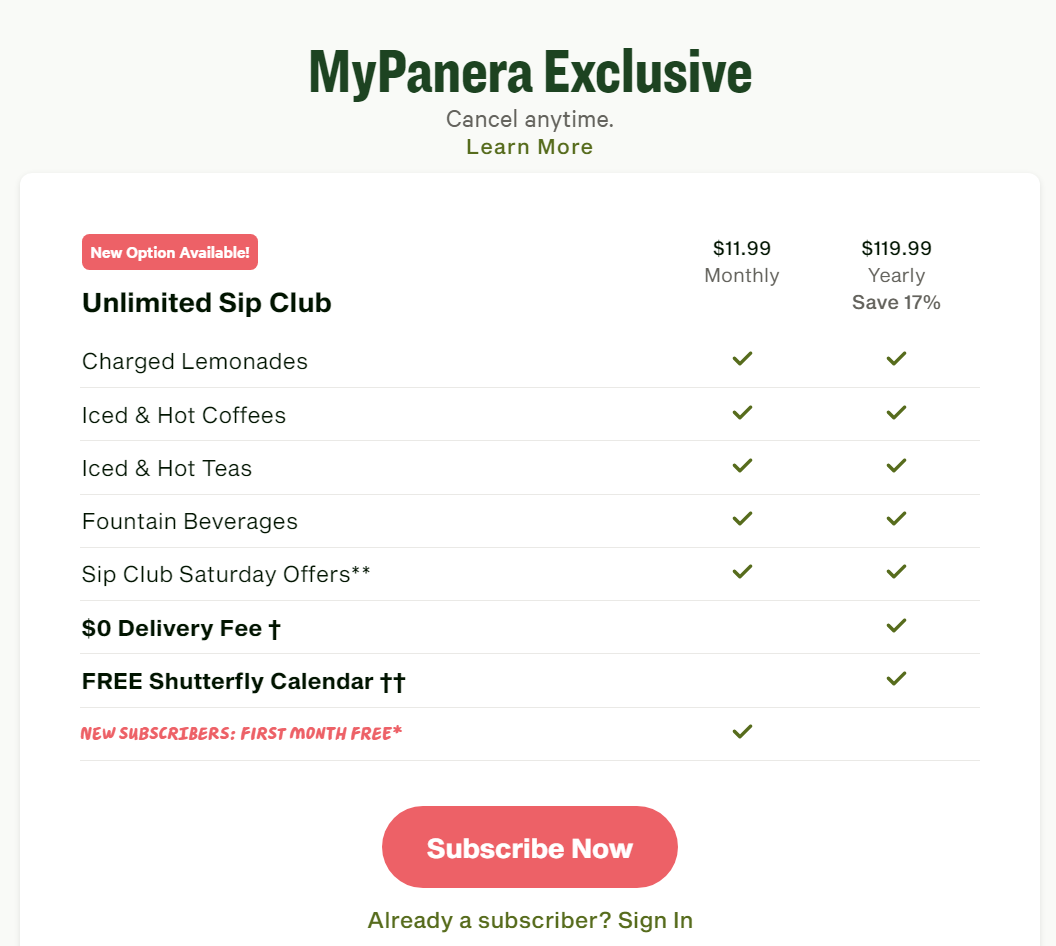

Example: Panera’s “Unlimited Sip Club” subscription

For $12/month or $120/year, this strategy gives a free beverage per visit to subscribers (note how “per visit” subtly makes this beverage not really free, unless you were going to visit anyway!).

This subscription is also offered “free for 4 months”, “free for 3 months” and “free for 1 month” depending if you are an American Express cardholder checking offers, or just any subscriber. Just like Netflix’s ad-supported tier, they would probably give it to you for free for a long while if you could keep it a secret, because the money is not in the subscription price!

How much do all these free beverages really cost Panera? Everyone knows the actual cost of beverages is negligible, pennies per cup. This makes them the cheapest thing in the store for Panera to potentially give away in larger quantities, that affordable low-cost asset looking for better monetization. Of course, the real cost, if any, is from customers that would have purchased that lemonade for full price ($3-4 of pure profit), and now get it for free. But the targeting works great for Panera here too … those are likely the very “great customers” worth rewarding to keep / bring in the restaurant a couple of extra times per month, and to convert in paying subscribers after the free trial!

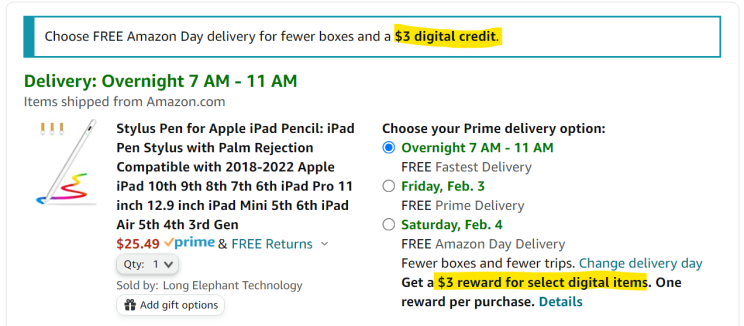

Example: Amazon’s “digital credit” nudge to save big on delivery costs and stimulate high-margin digital sales

How brilliant is this pricing power move? Amazon makes customers seemingly small in-cart offers: accept slower delivery and consolidating multiple Prime deliveries into one for a credit against “select digital purchases” typically in the $1-2 range.

In one fell swoop, it makes the customer happier with additional choice, it puts serious dollars of net profit back in Amazon’s pocket (by reducing packaging/labor/freight / delivery costs from multiple packages to one), AND puts a nudge in the customer’s account to make yet another (highly profitable) digital purchase with the “credit”.

Amazon effectively extends their offering design with choices for “how much do you really need/value Prime delivery for each purchase”? The word “credit” craftily makes it sound like a price reduction, and it looks for further segmentation. Just like Netflix’s customers willing to watch ads for a small “digital credit” in the subscription price are worth a lot more to Netflix in advertising dollars and the “credit” may convert additional customers that wouldn’t otherwise even be customers, Amazon generates both large cost savings and additional demand for profitable digital purchases from any customers who take the $1-$3 “credit” offer (the amount of credit “slides” with the number / size / cost of additional deliveries and “rush factor”). The “offer” is not just virtually costless for Amazon, it may in fact result in net revenue at high margins!

Move #3: Price pack & portfolio plan for inflation and softening demand

When inflation and other agents like supply-chain failures bring high-velocity changes to the supply-demand balance, brands need to evaluate diligently if their product portfolio choices expand or constrain their pricing power.

The most pressing analysis is whether a brand’s price pack architecture, or product line-up, provides coverage and margin-optimizing choices to anticipate “where the puck is going” in consumer preferences.

- Are products that drive large portions of our profit pool presented as binary choices “Purchase this: Yes/No”? If a consumer says “no thanks” to a brand’s higher price on one of its “hero skus” is she (and the pocket share / dollar contribution margin from her purchase / continued loyalty) lost for the brand?

- Or do we have “off ramp” options, products that she finds acceptable substitutes that allow us to keep both her customer relationship and healthy “alternative” dollars of contribution margin under our brand umbrella?

Depending on the location of the profit pools and specific threats to each one, brands may consider:

“Off ramp” optionality for hero skus

Particularly relevant for fashion (footwear & apparel), electronics, or other markets where brand & in-trends play a key role in the purchase decision, and the unit prices are “significant” for some budgets.

- If a SKU A drives millions of dollars in contribution margin, and its price is moving up over hurdle X that is significant to elasticity, should the brand first have SKUs B & C in place that may offer either lower price point, or more features, as “Off ramps”?

- Brands like Apple, Nike, Birkenstock, or General Mills are exceptionally adept here.

Club-size or family packs

For grocery, cosmetics and generally SKUs that are purchased less frequently and consumed over time. If consumers buy your product on average 1-2x / year, either as a treat or something they can “spread out” consuming over time … it makes sense to have options for consumers who are willing to leave a higher $ amount in revenue and contribution margin in one purchase, and reward them with a better price per unit of volume / value. This is even more compelling if your “regular size” hero SKU has been moving up in price significantly in response to inflation.

“Shrinkflation” packs

Particularly relevant for CPG / products that are frequent/habit purchases, where private label or lower-priced competitors present easily available choices to lure budget-sensitive consumers. This controversial tactic avoids drifting upwards into “unacceptable” price points, and leave it up to the consumer to do, or not, the diligence to understand that they’re paying more per unit of value.

Conclusion

This is a shortened list, with a number of other go-to pricing power moves necessarily left for future installments. Still, these examples should remind and boost conviction that there are always pricing power moves for every consumer brand to make. What will be your next pricing power move in 2023?

If your brand would benefit from partnering with experts to boost your pricing power, please reach out to us at EBITDA Catalyst … we live and breathe this stuff!

———————————–

?Please don’t forget to hit the “Subscribe” button to get all our newsletter updates in your feed.?