Summary

- The dispute between Pantone and Adobe has unnerved Adobe and many of its users, showing that key suppliers may successfully press for participation in economic gains from subscription pricing.

- With many price increases across the economy, both B2B and B2C brands asserting rationales of “increased value” should review their supplier relationships and prepare for key suppliers to perceive their own value has increased, too.

- In goods markets where price increases may result in profit gains while losing some volume, the volume loss risks impact suppliers economics … avoiding a “win-lose” outcome will require difficult conversations.

Pantone asks for a cut of Adobe’s success

For many years, it would have been easy to assume that Patone is simply another brand or trademark that Adobe owns. The ubiquity and seamless functionality of Patone color swatches and options in Adobe Creative Cloud, the suite of design apps from the company behind Photoshop and Illustrator, made it a valued, indeed relied-upon, asset for Adobe’s users. During this time, however, Adobe’s storied transformation to a SaaS / subscription model, revealed the value of Adobe’s offerings to be higher and higher, and Adobe’s dramatic increase in profitability and market value since 2012 has been the stuff of many case studies.

Turns out, Pantone is a separate company, with its own shareholders and profits to worry about. And as a provider of what may have become a “must-have” benefit in Adobe’s lineup of value claims, is it surprising that it, too, got the message that Adobe has found dramatically more willigness to pay (over time) in its subscription model? In fact, existing customers of Adobe who used Pantone colors (many of them), would be left with all those colors turning to black in all their previous, existing creations, without Pantone’s humble “ingredients” contributions to Adobe’s success. That is what “value” looks like, and what leverage is built on. So Pantone and Adobe have been in a months-long dispute, Adobe flexed its muscle and said it would take Pantone out of its offering, and users feel “taken hostage” in the dispute. Some are having to pay both Adobe and Pantone to avoid “losing” color in years worth of work.

Was this avoidable? Could Adobe have done more to lock in a key supplier rather than risk a high-stakes negotiation playing out while its users bear the brunt of the consequences? We don’t know, but there is value to every company out there to integrate thinking about suppliers in their pricing strategy.

How does this supplier “hostage taking” apply to other companies and markets?

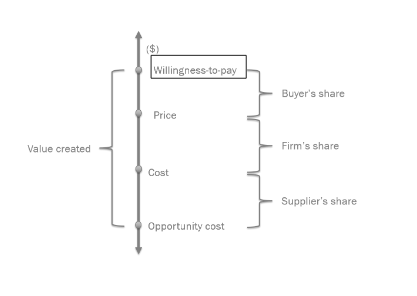

Any surplus harvested as differential between your customers willingness-to-pay (WTP) and your suppliers’ opportunity cost must be shared between your buyers/customers, your own firm, and your suppliers, as illustrated below. The lower part of this diagram has unfortunately often been forgotten, or assumed to get lower over time as suppliers are squeezed by competition, savvy procurement teams, and a “dependence” on firms that buy their offering. But suppliers are often businesses just like any other, looking for differentiating value to improve their own pricing power and surplus over time.

In the end, as any B2B relationship tends to, it boils down to alternatives (and other types of “leverage”), preparation, and negotiation savvy. Situations like Pantone/Adobe, where a supplier’s assets become so differentiated and depended upon as to put the Adobe’s of the world in a real “hostage” risk, are relatively few and far between. Regardless, firms who are about to, or already have, profited handsomely from pricing transformations or even simpler price actions, should at a minimum ask themselves:

- Which of our suppliers provides assets that could be “single points of failure” in our ability to supply our offering, or dramatically impact our customers’ perception of value?

- What is our realistic alternative set if one such supplier tests their own pricing power on us?

- What do we believe is “fair”, and what is “achievable” when it comes to sharing potential “growth” in our surplus with suppliers?

- What can we do to be more prepared / better positioned for that negotiation if our success invites sharing expectations in key suppliers?

- For goods markets with significant COGS and operational challenges to supply inputs, is ours the kind of success that actually hurts our suppliers? For example, if we raise prices expecting higher profit even with some volume declines, will our suppliers be hit w/ volume declines without any offsetting benefit from our higher prices?

Conclusion

In the current environment, it is typically the case that supplier and input cost increases flow upwards, with each buyer considering pricing actions as a result of cost pressures. In such a flow, Adobe could increase prices to its own customers to “cover” the higher cost of their Pantone “ingredient.” But of course Pantone appears to have much less of a case that it’s own costs have dramatically increased than, say, commodities-dependent consumer brands. It is more likely that Adobe’s massive success with pricing transformation created a “deal envy” situation in which Pantone, in retrospect, believes it charged too little for its value. It could well be right, and face an uphill battle getting a 900-pound gorilla to set a precedent of giving in.

It pays for any firm out there to plan for success: pricing can, and sometimes will, succeed in changing the game for the economics of your market, perhaps beyond anyone’s expectations. Like any profit pool, yours will attract more interest as it gets larger. Reviewing strategic supplier relationships and planning for success can pay rich dividends: hedging excess profits is a lot easier when nobody assigns a high probability to that scenario.

Want more EBITDA Catalyst insights?

Follow EBITDA Catalyst on LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/company/ebitdacatalyst/ or connect with any of us directly.

Check out our Pricing Quotes page, where you can submit your own favorite. If you are a pricing professional or someone who just thinks about pricing a lot, feel free to submit your own words of wisdom and we will quote YOU (if we find it quotable)! https://www.ebitdacatalyst.com/quotes-on-pricing/